Contents

Experiences in Integrative and Comparative Biology

Al Bennett and Edwin Cooper

Message from the President

John Pearse

Message from the Treasurer

Ron Dimock

Message from the Program Officer

Eduardo Rosa-Molinar

Message from the Past Program Officer

Linda Walters

Message from the Secretary

Lou Burnett

Divisional Newsletters

Comparative Biomechanics (DCB)

Comparative Endocrinology (DCE)

Comparative Physiology and Biochemistry (DCPB)

Developmental and Cell Biology (DDCB)

Evolutionary Developmental Biology (DEDB)

Experiences in Integrative and Comparative Biology

In this newsletter, we hear about some experiences from two former presidents of our Society, Al Bennett and Edwin Cooper. Edwin Cooper was president in 1983 and is a Distinguished Professor of Neurobiology in the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. Al Bennett was president in 1990 and is a Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and Dean of the School of Biological Sciences at UC Irvine. Drs. Cooper and Bennett served as presidents when we were the American Society of Zoologists and when presidential terms were for one year instead of the current two year terms. I hope you enjoy some of the experiences these distinguished scientists share with us.

- Boyhood Memories Imprinted Comparative Immunology - Edwin Cooper

- The Magic of Field Biology - Albert F. Bennett

Lou Burnett, SICB SecretaryBoyhood Memories Imprinted Comparative Immunology

Edwin Cooper

Laboratory of Comparative Neuroimmunology

Department of Neurobiology

David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA

University of California, Los Angeles

I remember recognizing early on my fate to become a biologist-a zoologist. A lot of keen observations actually stayed with me and contributed enormously to shaping my career. In Houston Texas, where I grew up, spring rains unearthed a wealth of animals that I found most fascinating. Earthworms are not well when they are waterlogged so that excess rain brought them out seeking penetrable but not soggy soil. I never learned or liked to fish, instinctively not wanting to sacrifice earthworms to serve as bait for a sport about which I had no interest. Little did I know that earthworms would become one focus of my life's work as a comparative immunologist demonstrating in them in the early 1960s for the first time that an invertebrate could destroy a transplant, heralding the field of invertebrate immunology and rattling the monolithic world of immunology-much like Metchnikoff did when he discovered phagocytosis down by the seashore in southern Italy in Messina to be precise.

Visits to my maternal grandfather's farm further piqued my fascination with earthworms. As he plowed fields for planting, I became increasingly interested in earthworms as tillers of the soil. Grandfather Porche even told me that they would regenerate should his plow split them! There was even more barnyard biology at the farm as I actually saw what later became widely accepted in ethology as imprinting. Sneaking in and out of the barn, I saw how young chicks would follow the mother hen responding to her clucks. Or I saw his beehives and the dancing workers.

When I did my early work, the world of immunology was no more receptive than it was with Metchnikoff. As open as scientists seem or profess to be, rocking the boat is not always greeted with cheers! Persistence was important to Metchnikoff and it was to me as well. Returning from immunology meetings I became more convinced that I was on the right track with my discovery of graft rejection. And I was not alone since this observation had been made by the Germans in the 1920s. Graft rejection in earthworms to them was a developmental phenomenon, mediated by "individuality differentials" so well explained in Leo Loeb's book: The Biological Basis of Individuality. This was different from my interpretation-the self not self-concept, governed my interpretations as did all of immunology following the credo of Nobel Laureate Sir MacFarlane Burnet. Following his immunologic surveillance idea, some still ponder how efficient is the invertebrate immune response since there is relatively little incidence of cancer in invertebrates. Then simultaneously with my own seemingly independent work, the French School of emerging comparative immunologists notably in Bordeaux (DuPasquier, Valembois and his student Philippe Roch-later my post doc, winner of the First von Behring Metchnikoff Prize in Immunology awarded by the Societe Francaise d'Immunologie) were also thymectomizing frog larvae and grafting earthworms!

Later in my career, my earlier barnyard interest in observing nature was translated into watching and documenting the effects of aggressive behavior in the edible fish Tilapia and how the response to aggressive encounters could depress the immune system-the beginnings of psychoneuroimmunology-and other evidence that there are connections between the immune, nervous and endocrine systems, through cross-talk and sharing of cell markers such as receptors and mediator molecules. Much later at UCLA I actually received funding from Norman Cousins (first Editor of Saturday Review and a popularizer of self healing), since he was interested in behavior. To my advantage I assembled an international team and published a lot on an altered immune responses in β or subordinate fish after exhaustive chasing and biting and ramming by the α or dominant fish. Our movies show this clearly and even when a single fish is allowed to confront itself in a mirror, it will recognize itself and do the very same attack strategies and attempt to defeat it showing the same behavioral moves! When seemingly frustrated, that single fish will suspiciously cast a gaze: frustrated trying to figure a next winning move?

Back to Houston and rains, what else did I see as a boy-the houses of crayfish, those piles and piles of mud sticking up like primitive mud houses, or in puddles, tadpoles that eventually sprouted legs and became frogs? Later my explorations would lead to a complete dissection of the immune system of the frog-the discovery of the thymus, lymph glands connected to gills that, because of their structure, clean up blood and provide a source of antibody-producing lymphocytes. Even more in the frog, with a high school student, we showed the presence of stem cells in bone marrow and their capacity to restore an immune system damaged severely by irradiation.

I received the BS cum laude in Biology from Texas Southern University in 1957 and was awarded a scholarship to Atlanta University for the MS in Biology. In 1958, I was accepted in the invertebrate zoology course at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole and did a project centrifuging the eggs of Chaetopterus, a marine annelid, (ideas from the early embryologist Dreisch: 1867-1941). I remember seeing the quotation of Louis Agassiz: "Study Nature Not Books!" I returned to Atlanta University and finished up my MS thesis in 1959 on differentiation of the embryonic chick otocyst on the chorioallantoic membrane of older chick embryos.

Clearly I had demonstrated a measure of focus that changed drastically after I had arrived eagerly in 1957. I had been so excited and had decided to do about 15 projects for my thesis! My major Professor Mary L. Reddick, Phi Beta Kappa and PhD. Harvard (student of Leigh Hoadley, zoologist and marine biologist) did her thesis on ear development in chicks. So in 1957 when I entered her office with my not so short list of proposed projects, she tore it into pieces, smoked her Lucky Strike and said in firm terms, "Mr. Cooper you will work on this!" (chick otocyst development!).

From Reddick's sharp ultimatum, (still did not daunt my enthusiasm and questioning at the ripe old age of 20 years!) I had learned then immediately before arrival at Brown in 1959 (finished the PhD in 1962) to sharpen my focus and quickly chose to work with Professor Richard J. Goss (another Harvard PhD in zoology and an authority on stem cells and regeneration in any animal that upon amputation of a part would grow it again: salamander limbs and deer antlers). No one had done one intriguing project that excited me tremendously. So I decided to try and grow the salamander regeneration blastema in tissue culture. However there was one interruption in the tissue culture experiments that proved to be beneficial and a major turning point that determined the course of my career. Goss had plans for me to live in a glass house in Maine.

Spending a couple of summers with Richard Goss at the Mt. Desert Island Biological Lab, Salisbury Cove, Maine was fruitful. On a foggy day in the summer of 1961, Goss shocked me to no end essentially withdrawing me from my blastema project and urging me that upon returning to Brown in the fall, to continue the immunosuppression project. Although hurt and disappointed and feeling faint that my unique work had been destroyed, I followed his advice, completed the project, later published in the journal Transplantation and finished Brown on time. Goss gave me two admonitions: he wanted me to finish a project, not stay on for my PhD forever and not do a thesis that needed to be wheeled in! -the blastema work was only giving me enough positive results to keep me enthused, but not convinced. Of course I was egged on at Developmental Biology Meetings, where I was encouraged to continue by greats in embryology like the late Professor Paul A.Weiss, Rockefeller University (formerly Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research).

Finishing up my Ph.D., I mulled the future. What kind of post-doc would I do? I thought - developmental biology? No because the blastema project had not been convincing and I was not sure about immunology, entering it without ever having had a course-modern immunology was not yet exploding as it has done since. Then one day in the Brown U library, I met Jane Oppenheimer, the embryologist (Fundulus! embryos were included on the 1975 Apollo-Soyuz space shuttle mission) and former president of ASZ, chatted with her in the stacks and she mentioned the thymus in fish.

I quickly thought why not? At that time, the current immunology explosion was just beginning with people removing the thymus in mice, rats, even opossums primarily by Jacques Miller. So I thought, thymus in fish, maybe also thymus in tadpoles and immunosuppression and all was beginning to gel.

Before leaving Brown, I prepared a post doc application to NIH (National Cancer Institute) and drove west to California to work with William Hildemann at UCLA. Although the proposal was for immunosuppression in fish, I actually wanted to thymectomize bullfrog larvae to suppress their immune response. But remembering my earthworms, I knew that they had no thymus, an organ of vertebrates, but surely they had to have some kind of immune response because they lived in soil-never mind the habitat. I reasoned that all living creatures should be able to defend themselves. So I dreamed: I will exchange skin grafts in earthworms to show rejection as others were doing in birds, mice and rats. Once again I was right. My sure project was the tadpole immune project, grafting and showing antibody synthesis-the bread and butter as Hildemann called it. Why? No one wanted to believe that I was demonstrating graft rejection in earthworms, so Hildemann was cautious!

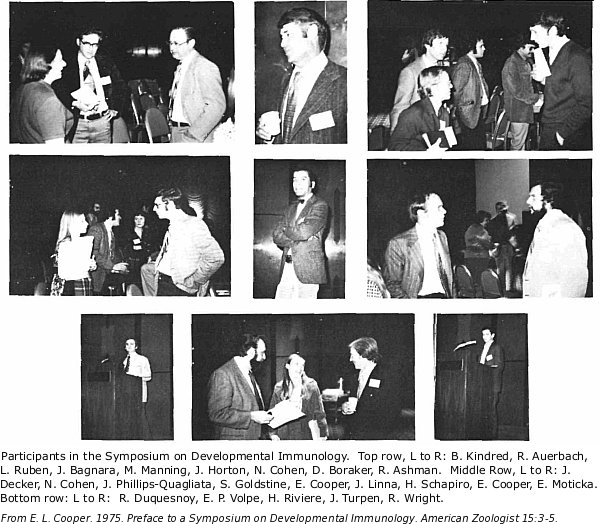

The American Society of Zoologists was a natural outlet for my interests and energy. Later I became involved with the International Society of Developmental and Comparative Immunology, serving as its president and editor of its journal, Developmental and Comparative Immunology. I am now working to bring the SICB along as a corporate member of the International Society of Zoological Sciences, which will be convening a Congress in Paris in August 2008.

Selected ReferencesCooper E. L. and Aponte, A. Chronic allograft rejection in the iguana, Ctenosaura pectinata. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1968; 128: 150-154.

Cooper E. L. The effects of antibiotics and x-irradiation on the survival of scale homografts in Fundulus heteroclitus. Transplantation 1964; 2: 2-20.

Cooper, E. L. 1968. Transplantation immunity in Annelids. I. Rejection of xenografts exchanged between Lumbricus terrestris and Eisenia foetida. Transplantation 6: 322-337.

Baculi B. S., Cooper E. L. Lymphomyeloid organs of Amphibia. II. Vasculature in larval and adult Rana catesbeiana. J Morphol. 1967; 123: 463-480.

Cooper E. L. Lymphomyeloid organs of Amphibia. I. Appearance during larval and adult stages of Rana catesbeiana. J Morphol. 1967; 122: 381-398.

Cooper E. L, Garcia-Herrera F. 1967. La organización de un laboratorio de investigación en embriologia e inmunologia comparada. Acta Med. 3: 59-67.

Cooper, E. L. and Schaefer, D. W. 1970. Bone marrow restoration of transplantation immunity in the leopard frog Rana pipiens. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 135: 406-411.

Hostetter, R. K. and Cooper, E. L. 1973. Cellular anamnesis in earthworms. Cell. Immunol. 9: 384-392.

Ramirez, J. A., Wright, R. K., and Cooper, E. L. 1983. Bone marrow reconstitution of immune responses following irradiation in the leopard frog Rana pipiens. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 7: 303-312.

Hildemann, W. H. and Cooper, E. L. 1963. Immunogenesis of homograft reactions in fishes and amphibians. Fed. Proc. 22: 1145-1151.

Cooper, E. L. and Hildemann, W. H. 1965. The immune response of larval bullfrogs (Rana catesbeiana) to diverse antigens. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 126: 647-661.

Cooper, E. L. 1967. Some aspects of the histogenesis of the amphibian lymphomyeloid system and its role in immunity. In: Ontogeny of Immunity, eds. R. T. Smith, R. A. Good and P. A. Miescher, Gainesville, University of Florida Press, 87-102.

Cooper, E.L. Comparative immunology. 1985. Past Presidential Address. Am. Zool. 25: 649-664.

Cooper, E.L., Klempau, A.E. and Zapata, A.G. 1985. Reptilian Immunity. In Biology of the Reptilia, eds. C. Gans, F. Billett and P.F.A. Maderson, 600-678, New York, John Wiley and Sons.

Cooper, E.L., Wright, R.K., Stein, E.A., Roch, P.J. and Mansour, M.H. 1987. Immunity in earthworms and tunicates with special reference to receptor origins. In Invertebrate Models, Cell Receptors and Cell Communication, ed. A.H. Greenberg, 79-103, New York, Karger.

Mansour, M. H. and Cooper, E. L. 1987. Tunicate Thy-1 an invertebrate member of the Ig superfamily. In Developmental and Comparative Immunology, Eds. E.L. Cooper, C. Langlet and J. Bierne, 33-42, New York, Alan R. Liss.

Mansour, M. H., Negm, H. I. and Cooper, E. L. 1987. Thy-1 evolution. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 11: 3-15.

Cooper, E. L. and Faisal, M. 1990. Phylogenetic approach to endocrine immune system interactions. In Unconventional vertebrates as models in endocrine research. eds. G.V. Callard and I.P. Callard, J. Exptl. Zool., Suppl., 4: 46 52.

Cooper, E. L. 1992. Innate immunity. In Encyclopedia of Immunology, eds. I.M. Roitt and P.J. Delves, 867-870, Jovanovich, Harcourt Brace Inc.

Cooper E. L. 1993. Basic concepts and the functional organization of the immune system. In Developmental Immunology, eds. E.L. Cooper and E. Nisbet-Brown, 3-30, New York, Oxford University Press.

Cooper, E. L. Mansour, M. H. and Negm, H. I. 1996. Marine invertebrate immunodefense response: molecular and cellular approaches in tunicates. Ann. Rev. Fish Dis. 6: 133-149.

Cooper, E. L. 1997. Comparative Immunology of the Integument. In Skin Immune System, ed. J. D. Bos, 18-39, Boca Raton, CRC Press.

Cooper, E. L., Kauschke, E. and Cossarizza, A. 2002. Digging for innate immunity since Darwin and Metchnikoff. Bioessays 24: 319-333.

de Eguileor, M, Tettamanti, G., Grimaldi, A. Ferrarese, R. Perletti, G., Valvassori, R., Cooper, E. L. Lanzavecchia, G. 2002. Leech immune responses: contributions and biomedical applications. In: Cooper EL, Beschin A, Bilej M, editors. A new model for analyzing antimicrobial peptides with biomedical applications. Amsterdam: IOS Press: 2002, 93-102.

Cooper, E. L. 2003 Comparative immunology of the animal kingdom. In The New Panorama of Animal Evolution, Proceedings XVIII International Congress of Zoology, eds: A. Legakis, S. Sfenthourakis, R. Polymeni and M. Thessalou-Legaki, Pensoft, Sofia, 117-125.

Cooper E. L. Comparative Immunology. Integr Comp Biol 2003; 43: 278 - 280.

Rosas, C., Cooper, E. L., Pascual, C., Brito, R., Gelabert, R., Moreno, T., Miranda, G. and Sánchez, A. 2004. La condición reproductiva del camarón blanco Litopenaeus setiferus (Crustacea; Penaeidae): Evidencias de deterioro ambiental en el Sur del Golfo de México. In.: Diagnóstico ambiental del Golfo de México, Secretaria de Medio Ambiente y Recursos, Instituto Nacional de Ecología, Instituto de Ecología, eds. M. Caso, Irene Pisanty y Ezequiel Ezcurra, 789-822, Mexico, A.C., Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies, Vol. 2.

Cooper, E.L. (ed.) 1974. Invertebrate Immunology. Contemporary Topics in Immunobiology Vol. 4. New York: Plenum Press, 299 pp.

Cooper, E. L. 1976. Comparative Immunology, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice- Hall, 338 pp. (Translated into Russian, 1980).

Wright, R. K. and Cooper, E. L. (eds.) 1976. Phylogeny of Thymus and Bone Marrow-Bursa Cells. Amsterdam, Elsevier/North Holland, 325 pp.

Gershwin, M. E. and Cooper, E. L. (eds.) 1978. Animal Models of Comparative and Developmental Aspects of Immunity and Disease. New York, Pergamon Press, 396 pp.

Cooper, E. L. 1982. General Immunology. New York: Pergamon Press, New York, 343 pp.

Cooper, E. L. and Brazier, M. A. B. (Eds.) 1982. Developmental Immunology: Clinical Problems and Aging. UCLA Forum in Medical Sciences, Vol. 25, Academic Press, New York, 321 pp.

Cooper, E. L. (Editor-in-Chief) and van Miuswinkel, W. B. (Guest Editor) 1982. Immunology and Immunization of Fish. Dev. Comp. Immunol. Suppl. 2: 255pp.

Cooper, E. L. and Wright, R.K. (eds.) 1984. Aspects of Developmental and Comparative Immunology II. Proc. 2nd Int. Congr. Int. Soc. of Dev. Comp. Immunol., Suppl. 3, New York, Pergamon Press, 280 pp.

Cooper, E. L., Langlet, C. and Bierne, J., (eds.) 1987. Developmental and Comparative Immunology, Alan R. Liss, N.Y., 180 pp.

Zapata, A. G. and Cooper, E L. 1990. The Immune System: Comparative Histophysiology. Chichester , England: John Wiley & Sons, 334 pp.

Cooper, E. L. 1990. General Immunology (Japanese Translation). Japan: Nishimura Co. Ltd., 324 pp.

Cooper, E. L. and Nisbet-Brown, E., 1993. Developmental Immunology. New York: Oxford University Press, 480 pp.

Vetvicka, V. Sima, P., Cooper, E. L., Bilej, M. Roch, P. 1993. Immunology of Annelids. Boca Raton, CRC Press, 300 pp.

Beck, G., Habicht, G.S., Cooper, E.L. and Marchalonis, J.J. (eds.). 1994. Primordial Immunity, Foundations for the Vertebrate Immune System. New York: New York Academy of Sciences, 376 pp.

Cooper, E. L. 1996 (ed) Invertebrate immune responses: Cells and Molecular Products. In: Adv. Comp. Environ. Physiol. 23: 1-216.

Cooper, E. L. (ed.). 1996. Invertebrate immune responses: Cell Activities and the Environment. In: Adv. Comp. Environ. Physiol. 24: 1-249.

Beck G, Sugumaran M, and Cooper, E.L. (eds). 2001. Phylogenic Perspectives on the Vertebrate Immune System. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology vol. 484. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers 2001.

Cooper, E. L., Beschin, A. and Bilej, M. A new model for analyzing antimicrobial peptides with biomedical applications. Amsterdam, IOS Press 2002.

The Magic of Field BiologyAlbert F. Bennett

Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology

University of California, Irvine

I was never a born biologist. I did not collect insects, watch birds, or chase frogs. I was a rather bookish boy, inclined more to remain indoors, rather than rambling around outside. I liked reading about animals, but it was a more intellectual than practical attraction. All that changed for me in college. While still a sophomore, I began doing field work as a laboratory assistant for Bill Mayhew at the University of California Riverside and spent a lot of time camping in the desert. One morning I remember waking up at sunrise and finding myself staring directly into the face of a kit fox, who seemed less excited by the experience than I was. By the end of that summer of noosing lizards and chasing snakes, I felt the transformative magic of being with animals in their world. From that point, I knew my calling and my career.

I have had the great fortune be able to undertake research expeditions to study animals in the field in North, Central and South America, Australia, and Africa. And it has been a privilege to be able to do this in the accompaniment of great friends, mentors and colleagues. In particular, my time in the field with my graduate advisor, Bill Dawson, studying the thermal physiology of wallabies, birds, and lizards in Australia was among the most rewarding and enjoyable experiences of my graduate career.

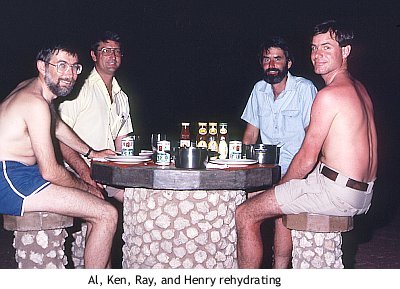

Here I want to highlight just one of those expeditions. This was my first trip to Africa. Ray Huey conceived and planned the expedition, which included Ken Nagy, Henry John-Alder, and me. We went into the Kalahari Desert, on the border between Botswana and the Republic of South Africa, to compare the physiology, behavior, and energetics of two closely-related species of lizards, one of which was a sit-and-wait and the other, a widely-foraging predator. This was back in the good old days, when two species comparisons without a phylogeny were still considered respectable. We spent a month sweating through hot days, watching animals daily and using doubly-labeled water to measure field metabolic rates, energy intake, and water turnover.We converted our kitchen into a "controlled temperature room" by turning the burners and oven on full blast and regulated the temperature of our lizards in a "chamber" constructed of a cardboard box and a hair dryer. We measured speed and endurance on an ersatz racetrack and treadmill. You learn to improvise and invent and make do, lemons become lemonade, and duct tape becomes the tool of choice. It was challenging and fun, exhausting and incredibly intellectually alive all at once. Part of my mind was always concentrated on the data being collected. Bob Josephson once said that as he collects data, he envisions how it will stand up to the statistical analysis and how it will look in the published figures, and I realized that is always how I worked as well: be sure that you have a sufficient amount and then move on.

Looking back on that trip, however, it is not actually the lizard study that draws my thoughts. More what I remember is just being there in the field, in Africa. We had a memorable welcome to our field site. I was walking the area looking for lizards, when a leopard growled and jumped out of a bush not 50 meters from me. No gun, no run. I was so dumbfounded that my first thought was to call out to Ray to come over to see it. It snarled at me and then ran off. About 3 seconds later the adrenalin hit, my heart nearly exploded, and my legs gave out. Only then did I realize the danger; before that it was all wonder. Later we saw the leopard often, with kills up in a tree. As we drove in to work in the morning, we shared the road with brown hyenas going to their den to sleep. Later we found their den, and in the late afternoon would park by it and watch them play with their pups before going out on a hunt. We saw an enormous mustard yellow cape cobra, nearly 2 meters long, climbing a tree to raid weaver finch nests. Lion were common, including males with enormous black manes. At the edge of our study site was a large acacia tree under which Ray had once seen a lion with a kill on a previous trip. He told us about that just once too often, and for the rest of the trip one of us would point out the tree and tell the story to the others twice a day. There was a lot of that kind of kidding and humor, and it helped to melt the frustration and exhaustion associated the long hot days. We played a lot of music while we worked. To this day I cannot listen to the Rolling Stones play Start Me Up without going immediately back in my mind to the dry bed of the Nassob River, where we listened to Tattoo You as we watched ground squirrels using their tails as parasols to shade themselves from the sun. My most enduring image of the trip is driving back to camp at high speed late one afternoon, passing eland and gemsbok, cheetah and lion, looking at enormous mauve thunderheads blotting out the setting sun, promising rain that never arrived. What a privilege it was to see that and be part of it, especially with such a fine group of companions.

George Bartholomew once said that Africa is special and pulls you in like no other place. That is certainly true and part of what made this expedition so memorable. But part of it also just being in a natural environment with animals living their own lives outside of human needs and concerns. It is always magical to enter their world and a privilege to be permitted to share it and to try to understand in some small measure what it is like for them to live there. As rules multiply and natural areas shrink and change, it is more difficult to do, but it remains both rewarding and renewing.

Huey, R. B., A. F. Bennett, H. B. John-Alder, and K. A. Nagy. 1984. Locomotor capacity and foraging behaviour of Kalahari lacertid lizards. Anim. Behav. 32: 41-50.

Bennett, A. F., R. B. Huey, and H. B. John Alder. 1984. Physiological correlates of natural activity and locomotor capacity in two species of lacertid lizards. J. comp. Physiol. 154: 113-118.

Nagy, K. A., R. B. Huey, and A. F. Bennett. 1984. Field energetics and foraging mode of Kalahari lacertid lizards. Ecology 65: 588-596.

Bennett, A. F., R. B. Huey, H. B. John-Alder, and K. A. Nagy. 1984. The parasol tail and thermoregulatory behavior of the cape ground squirrel (Xerus inauris). Physiol. Zool. 57: 57-62.